- Home

- Judith Summers

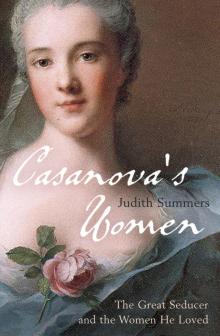

Casanova's Women

Casanova's Women Read online

CASANOVA’S WOMEN

The Great Seducer and the Women He Loved

JUDITH SUMMERS

CONTENTS

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

PREFACE 2 April 1798

ONE Zanetta

TWO Virgins of the Veneto

THREE Donna Lucrezia

FOUR Bellino

FIVE Henriette

SIX M.M. and C.C.

SEVEN Manon Balletti

EIGHT The Marquise d’Urfe

NINE Marianne de Charpillon and Pauline

TEN Sophia Williams and Teresa Imer Cornelys

ELEVEN 4 June 1798

Brief Chronology

Notes

Bibliography

Picture Credits

Author’s Note

A Note on the Author

By same Author

Imprint

For Donald

Throughout my life, cultivating the pleasures of my senses was my main occupation; I have never found any other more important. Feeling that I was born for the opposite sex, I have always loved it, and I have done everything I could to make myself beloved by it.

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova

PREFACE

2 April 1798

IT IS A PERFECT setting for love, or at least seduction: a bench in an ivy-covered arbour in the grounds of a French chateau. A fountain of cherubs stipples the surface of a stone carp pool, while swallows swoop above, fishing the air for gnats. Beyond the water, an avenue of yew trees leads the eye between velvet lawns towards distant hills. Hidden somewhere in the foliage, a blackbird serenades the approaching dusk with his clear sweet melody.

The late evening sunlight pours over Giacomo Girolamo Casanova de Seingalt, gambler, adventurer and self-confessed libertine. It warms his long muscular limbs through his lace-trimmed shirt and silk knee breeches and glints off his diamond coat buttons and the jewelled buckles on his shoes. He feels relaxed and light-headed, and is experiencing a moment of exquisite happiness. For sitting beside him in this bucolic idyll is a young dairymaid, the most alluring he has ever seen. Emerald eyes and rose-pink lips smile shyly at him from a face every bit as well-chiselled and delicate as that of a French princess. A mass of long raven hair, fastened on top of her head with a single hair pin, tumbles loosely on to her shoulders in suggestive disarray. Two well-formed breasts, each the perfect size to fit in one of Casanova’s large palms, strain against the bodice of her calico dress, and her hands and arms, which are bare up to the elbows, are as flawless and pale as cream.

Casanova breathes in the faint odour of the dairymaid’s sweat, a smell as fragrant as cut grass. He has been aching to possess this treasure from the first moment he saw her two days ago. Since then he has paid her assiduous yet very correct attention, treating her not at all like the servant she is but like the grand lady she was obviously born to be. She has responded with commendable humility and discretion which has redoubled his feelings for her, and he can tell by the way she blushes when she looks at him that she is as smitten by him as he is by her.

He expected no less. Unusually tall, as handsome as a prince and as dark-skinned as a North African, Casanova is aware that he has the kind of presence that stops both men and women in their tracks. At the age of thirty, he is a vital predatory animal in his prime. Coupled with his larger-than-life personality he has a surprising sensitivity, and an unquenchable thirst for all that life has to offer, good or bad. With one notable, damaging exception – his own mother – women like, love or adore Casanova, and one has only to spend a few minutes with him to understand why. As well as good looks he possesses the rare gift of befriending women. He has the knack of addressing them as if they were his equals, and undressing them as if they were his superiors. Unlike many men of his day, he knows what motivates and pleases women and is in tune with their fears, hopes and desires. Sometimes cannily, sometimes unconsciously, Casanova uses his instinctive understanding of the female sex to get what he wants from them. In his long career as a womaniser he learned early on that he has only to be a sympathetic listener to worm his way into a heart or underneath a skirt.

But this evening Casanova wants only one woman, this lovely and innocent dairymaid. A connoisseur of virgins, he is certain she still is one. Furthermore he is convinced that she is the woman he has been searching for since his childhood, the one being who can fill the gnawing hollow inside him and enable him to live at peace with himself. He is not inventing this simply in order to bed her. At this particular moment – the moment preceding seduction – Casanova truly believes that he is in love with her. And since she does not know any better, she is convinced of it as well.

Casanova’s practised eye can tell by her smile that she is as ripe for picking as the apricots weighing down the espaliered fruit trees trained against the chateau walls. He murmurs an endearment in her ear. He tells her how much he feels for her, and squeezes her hand. When she insists that she is saving her maidenhood for marriage he spontaneously and sincerely declares, ‘Then let us be married without delay!’ Though it is engraved upon Casanova’s heart thatmarriage is the tomb of love, a union between himself and this delectable creature must certainly be the exception. To make an honest woman of her and save her from a life of servitude is to be his happy fate.

‘But let us not wait for formalities!’ he says. ‘Let us seal our union before God right now, and go to the priest later!’ As he pulls the girl towards him she smiles up at him with complete trust. With a speed born of years of experience he unties the apron fastened around her waist and casts the garment on to the grass. Casanova does this so naturally, and with such abandon, that instead of resisting him she just laughs. Next, he manoeuvres an arm around her plump shoulders, draws her face towards his and inhales her violet-petal breath. For the first time he kisses her lips – not a passionate or probing kiss that might set her running away in fear, but lingeringly, softly, with a tantalising expertise, so that her lips feel nothing more threatening than the delicate caress of butterfly wings. While he is doing so, Casanova inches her on to his lap. Before she can protest, before she is even aware what he is about, he has unlaced her bodice, slipped his hand inside her chemise and freed her straining breasts from their linen prison.

His treasure sighs deeply and mutters in a guttural voice, ‘Come on, sir! Hurry up and open your mouth. I don’t have all day to muck around doing this.’

Gaunt, sallow-skinned and propped up in a chintz armchair in his bedroom in Dux Castle in Bohemia, Giacomo Girolamo Casanova, septuagenarian, blinks open his eyes, lets go of this memory of a seduction long past and does what he is ordered to. He has been seriously ill for some weeks and is too feeble to feed himself. However, since the local doctor, fool that he is, has ordered that Casanova must take some form of nourishment he is having to undergo the indignity of being fed.

Magda, the pasty-faced and entirely charmless kitchen maid who has been allotted this onerous task, dips a spoon into the bowl of soup balanced in her lap and transports the contents up to Casanova’s lips. The old man grimaces. On the day before his birth, his mother had had a strong desire to eat crayfish, and consequently a soup made of the creatures has always been one of his favourite dishes. But lately he has lost his taste for it. This batch is particularly unappetising: oily, over-salted and, since it has been carried up here from the far-off kitchen, cold and viscous to the point of being congealed. Casanova can scarcely bring himself to swallow it. As it sits unpleasantly in his mouth, a drop dribbles down his chin where it hangs like spittle until Magda swats it away with a napkin and a disapproving curse.

Today is Casanova’s seventy-third birthday, and he is already suffering from the debilitating painful bladder

disorder which will claim his life in two months’ time. Considering how many deceived husbands and women must have wanted to kill him during the course of his long life it is ironic that he is destined to die of a urinary infection in the safety of his own bed.

Casanova barks out a reprimand. Has Magda no manners or finesse? Does she not know who he is? She wipes her nose on the back of her hand and stifles a laugh. If she has heard this once she has heard it twenty times over. ‘Of course I know who you are, sir,’ she retorts, trying to keep a straight face as she raises another spoonful of soup to his lips. ‘You must think I’m simple. You’re Monsieur Casanova, the librarian. You work here at Count Waldstein’s castle. Just like me.’

If there is one thing that rouses Casanova to anger it is insolence. Weak as he is, he dashes Magda’s hand away from his face. Soup splatters over her apron and across the floor, and recriminations and insults fly from both sides. Leaping up, Magda bangs the soup bowl back on to the tray, flounces out of the room and runs down to the kitchen in tears, less upset than she is looking forward to sharing the story with the other members of the castle’s staff.

Left alone, Casanova throws himself against the back of his chair in a paroxysm of anger directed as much against Fortune as against the stupid, ugly girl. He rails against the poverty which has forced him to accept a position in service. He curses his pain, his loneliness, his fate. Why has he ended up living among uneducated strangers who despise him? Why does no one in this godforsaken town appreciate the calibre of man he is?

The crayfish soup, however unpleasant, is easier to stomach than old age, a humiliating state Casanova has been reluctantly but inexorably embracing for the past three decades. Once, he had felt invincible. Born into the despised milieu of a poor theatrical family at a time when class was the defining feature of a man’s existence, he reinvented himself as the equal of any aristocrat and rose to become one of the most erudite intellectuals of his age. No high-born philosopher could outwit him, no titled duellist touch him with their point, no wealthy gambler get the better of him at cards, and no woman, however sophisticated, resist his advances for more than a week. Striking-looking, brilliant, vain and proud, Casanova talked his way into all the best drawing-rooms of Europe and under many of the finest lace-trimmed silk petticoats. Senators, empresses and princes invited him into their salons. King George III of England received him at St James’s Palace. Frederick the Great discussed taxation with him. Pope Clement XIII joked with him, and conferred on him the Papal Order of the Golden Spur. Paris’s wealthiest widow kept Casanova in diamonds. Madame de Pompadour favoured him. Voltaire and Rousseau talked with him, Benjamin Franklin sat next to him in the Louvre, and he had not one but three interviews with Catherine the Great, Empress of all the Russias.

Women – scores and scores of beautiful women whose names have been lost to history – welcomed him into their beds.

Equally at ease in a palace, a merchant’s house or a brothel, and most at home between a woman’s legs, Casanova successfully straddled the worlds of the high life to which he aspired, and the low life into which he had been born. Steering a course through both, but putting down roots in neither, he followed only one precept in his life – to go where the wind blew him – and he crisscrossed the continent of Europe as often as the migrating birds. En route he plied a good number of professions, but although he was a polymath with infinite capabilities he had little staying power, so in the end he became master of none. At one time or another he was a priest, a spy, a soldier, a playboy. In Rome he became secretary to a famous cardinal. In Paris he talked his way into becoming a financial adviser to the French government, founded a highly profitable national lottery for them and, on his own account, opened a factory that made hand-painted wallpaper. In the business centre of Amsterdam he dealt in shares as well as cards, and had equal success in both. Addicted to gambling from an early age, he frittered his fortunes away like sand in the wind. He was generous to a fault and fatally extravagant, especially when the money he was spending was not his own.

An historian, philosopher and writer, Casanova published books and pamphlets in Paris, Prague and Dresden, edited a literary journal in Venice, wrote a history of Poland and translated Homer’s Iliad into his native dialect. Although he had no particular talent for music, he once took a job as a violinist in a theatre, work that he found humiliating but which nevertheless led to his greatest-ever stroke of luck. Somehow able to turn almost any situation, however unpromising, to his own advantage, he was an adventurer whose imprisonment and subsequent escape from the most secure prison in Europe, Venice’s I Piombi, earned him fame and admiration as well as notoriety. Strangers of all classes were as captivated by the intriguing, impressive figure he cut as they were enchanted by his magnetic personality and witty conversation; as one female stranger wrote breathlessly after dining with him in Lyon, ‘We hung on his lips.’ Although he had an extraordinary gift for intimate friendship, if someone dared to slight him he would become their enemy for life. Unable to fathom his character or to pinpoint his exact position in the world, his acquaintances gossiped about him from Salerno to London, sometimes admiringly, at other times critically. Was Casanova a pauper or a millionaire, a man of principle or a dishonourable, dishonest rogue? At ease with his own contradictions, he worshipped the truth and yet was happy to be a consummate conman whenever it suited him, claiming that he deceived the foolish only in order to make them wise. He became a Freemason, a Rosicrucian and a freethinker whilst remaining at heart a Christian. Though he derided the superstitions of others, he studied alchemy and the Kabbalah, and led people to believe that he was a mystic and a sage. Countesses asked him to predict their future, and duchesses consulted him on intimate matters of health. Even intelligent men fell for Casanova’s clever deceptions and unwittingly enriched his purse; and he easily convinced the credulous that he could turn base metal into gold.

All in all, Casanova reflects from his armchair in Dux Castle, these things are substantial achievements for a cobbler’s grandson whose own uneducated mother dismissed him as an imbecile.

But by far Casanova’s greatest achievement has been as a womaniser. He has had women in almost every city, town and port on his remarkable 64,000-kilometre journey around Europe, and sometimes on the coach journeys in between. He has slept with actresses and opera singers, housekeepers and shopkeepers, a slave and a serf, lawyers’ wives and businessmen’s daughters, noble women and fallen women, high-class courtesans and common whores. He has made love to experienced married ladies and he has deflowered countless virgins. He has enjoyed sex with women in their late fifties, and – a particular predilection of his – girls as young as eleven years old.

Ancient taboos have proved an aphrodisiac rather than a barrier to Casanova, who has made love to two nuns, his thirteen-year-old niece and his own grown-up daughter, an encounter that, very probably, led to him siring his own grandson. No sexual or romantic challenge has proved too great for him: once, quarantined in a lazaretto in Ancona, he indulged in heavy petting with a female slave through a hole in a balcony floor, and, on another memorable occasion, with a young schoolgirl through the iron bars of a convent grating.

In his active days Casanova enjoyed a conquest as much as a victory. Relegating the possibility of failure to the realm of impossibilities, he refused to take no for a final answer. If he had the will to woo someone, he would find a way. There was not one woman in the world, he believed, who could resist the attentions of a man determined to make her fall in love with him, and experience taught him that in ninety-nine out of one hundred cases he was right. Scores of women from Amsterdam to Zurich who initially refused to sleep with him later willingly defied their fathers, husbands, lovers or convention in order to throw themselves at his feet.

Yet Casanova was seldom satisfied with winning a woman’s body. What he wanted, far more than sexual satisfaction, was to win her heart. And more often than not, he claimed that prize as well.

Casa

nova was born into an age of intrigue and gallantry, an age when love is the prerogative of the rich, and sex one of the few pleasures available even to the poor. The Church preaches abstinence outside marriage, but few people take any notice of its sermons, even the priests and bishops, many of whom lack religious vocation and have only embarked upon a clerical career at the behest of their families. Since enlightened minds see sex as a natural, pleasurable act which leads only to happiness, male philandering is acceptable and male chastity is almost non-existent: as the Methodist preacher John Wesley writes, ‘How few can lay claim to it at all?’

Love is a widely available commodity, and attitudes to sex are liberal. Pornographic engravings are on display for all to see in the windows of London’s print-shops and female armies made up of thousands of whores patrol almost every European city. They range from desperate streetwalkers who will pull up their skirts in a doorway, on a bridge or behind a tree for only a few pennies to well-bred prostitutes who demand courtship and high fees. In the Swiss city of Berne, ladies of pleasure step naked into the spa baths with their clients. In London, where there are more than one hundred brothels within the vicinity of Drury Lane alone, publications such as Kitty’s Atlantis, the Whoremonger’s Guide and the Covent Garden Magazine or Amorous Repository list the women’s names and whereabouts, along with their prices and sexual specialities. Paris has its own such publication: the Almanack des Adresses des Demoiselles.

Rich men who want more than relief sex – or sex with less risk of disease – can look for a lover among the better class of courtesan, or the virgin daughters of the working classes, or among their servants, or even among their peers. In the second half of the eighteenth century every woman seems open to their approaches, from high-born duchesses to the wenches who wait on them. For to have a lover is considered a status symbol in sophisticated European circles where marriage is usually little more than a business arrangement forged by one’s family, and where only the female servants of the rich, who build up their own dowries from their wages, have the freedom to choose their own spouses. As Lord Chesterfield advises his son, ‘Un arrangement, which is, in plain English, a gallantry, is at Paris as necessary a part of a woman of fashion’s establishment as her house.’ No king is a king without at least one official mistress, and no prince or duke can hold up his head in public if he does not have a beautiful courtesan in tow. Even the Russian empresses take lovers, Catherine the Great at least twelve of them.

Casanova's Women

Casanova's Women